PANEL OF EXPERTS

Ms Dimitra Birthisel Corporate Counsel and Board Secretary, Museum Victoria

Ms Jasmine Cameron Assistant Director-General, National Library of Australia

Mr Tony Caravella Member, Social Security Appeals Tribunal

Mr Joseph Corponi Senior Project Manager, Arts Victoria

Mr Frank Howarth Director, Australian Museum

Dr Matasha McConchie Director, Collections Development, Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts

Mr Peter Morton Executive Officer, Powerhouse Museum

Mr Russell Smylie Executive Officer, Australian National Maritime Museum

Mr Tim Sullivan Deputy CEO and Museums Director, Sovereign Hill Museums Association

INTRODUCTION

What is Governance?

Governance generally refers to the processes by which organisations are “directed, controlled, and held to account”[1].It is underpinned by the principles of openness, integrity, and accountability[2]..

Openness is required to ensure that stakeholders can have confidence in the decision-making processes and actions of organisations, in the management of their activities, and in the individuals within them. Being open through meaningful consultation with stakeholders/shareholders and communication of full, accurate and clear information leads to effective and timely action and stands up to necessary scrutiny[3]..

Integrity comprises both straightforward dealing and completeness. It is based upon honesty and objectivity, and high standards of propriety and probity in the stewardship of funds and resources, and management of an entity’s affairs. It is dependent on the effectiveness of the control framework and on the personal standards and professionalism of the individuals within the entity. It is reflected both in the entity’s decision-making procedures and in the quality of its financial and performance reporting.[4].

Accountability is the process whereby organisations, and the individuals within them, are responsible for their decisions and actions, including their stewardship of funds and all aspects of performance, and submit themselves to appropriate external scrutiny. It is achieved by all parties having a clear understanding of those responsibilities, and having clearly defined roles through a robust structure. In effect, accountability is the obligation to answer for the responsibility conferred.[5].

More recently governance has been described as “the system by which companies are directed and managed. It influences how risk is monitored and assessed, and how performance is optimised”[6].. Governance is concerned with structures and processes for decision-making, control and behaviour at the top of organisations. Effective governance is also essential for building consumer and community confidence in an organisation, which is in itself necessary if the organisation is to be effective in meeting its objectives.

Whilst there is no single model of good governance, there are a number of common elements that underlie good governance practices[7]. These are outlined in this chapter.

Governance in Public Sector Organisations

Public sector entities have to satisfy a complex range of political, economic and social objectives, which subject them to a different set of external constraints. They are also subject to forms of accountability to various stakeholders, including Ministers, other government officials, the electorate (Parliament), customers and clients, and the general public.

Government relies on governing board members of statutory corporations and authorities to meet desired Government outcomes by strategically directing government resources. In return, all board members are required to perform their duties honestly, openly, in good faith and with a high order of care and diligence. These performance requirements can be referred to as principles of governance which are derived from the common law. Failure to adhere to corporate governance requirements could result in criminal and/or civil penalties.

To be effective, governance as a notion should be tailored to, and interpreted within, the specific context of an organisation’s structures, objectives, relationships and activities.

There are several aspects to the successful governance of a non-profit organisation:

- Ensuring that everyone involved has a clear idea of their expectations, roles and responsibilities in relation to the objectives and running of the organisation and the management of its finances;

- Recognising and addressing the problems that can occur in organisations that depend heavily on the commitment and enthusiasm of a few individuals.

- Establishing and managing an effective working relationship between the individual members of the board so as to make the most of the skills and talents of its members;

- Creating and maintaining the relationship between the board, the staff and volunteers of the organisation to ensure that there are proper lines of communication, accountability and responsibility established and maintained;

- Ensuring that there are clearly defined ethical standards in place for both staff, management and board;

- Educating the board and management in the politics, ethics and controversial issues facing collection institutions.

This section outlines the purpose of the board; selecting the board; duties of board members; helping the board to work more effectively; and dealing with problem board members.

Purpose Of The Board

The board has a multiplicity of purposes, the foremost of which is a management role in relation to the organisation and its staff. Although these will differ depending on the nature and size of the organisation the main responsibilities of the board generally include the following:

- Establish and review the structure of the organisation. One might say that it is hardly the role of the board of a statutory institution to establish and review its own structure. This is a role generally undertaken at a government departmental level.[8] On the other hand, in organisations the review of the constitution is something that the board should regularly, if infrequently, undertake.

- Define and review the policies and practices of the organisation. These include policies concerning the cultural objectives of the organisation but also policies relating to the employment of staff, the relationship of the organisation to other institutions and to the public, the raising of funds, and the financial management of the organisation;

- Devise and review the strategies for implementation of the organisation’s objectives. The organisation’s strategy is something best generated by the board – taking advice from management. The healthy board takes time for personal reflection, listens to the organisation’s management, staff and stakeholders and considers the views of any informed and interested thinkers and commentators – and then develops its own strategic goals. It doesn’t just ratify the plan served up by management;

- Review the performance of the organisation against the strategic plan. The strategic plan maps the direction of the organisation and the targets that the management is expected to meet;

- Advocacy and representation (in particular the relationship between government, key stake holders and board) is critical. The CEO of the organisation might well be the media face of the organisation but it is the chair (or president), supported where necessary by select board members, who is responsible for representation of the organisation within government and other strategic relationships.[9]

- Establish and maintain clearly defined lines of communication, delegation, and responsibility[10].

- Help raise money for the organisation. All collecting institutions need to make money beyond the funding that they receive from government. The sources for earned income are very diverse and it is important that some members of the board have skills that are relevant to this need. The American approach is to leave governance to an executive committee and use board membership as a reward or bait for philanthropy. Under the Australian legal system that confers considerable liability on board members, governance must be the primary role of any board member. Raising funds is important, but secondary to governance.[11]

- Provide the organisation with a network of contacts. The effective board has tentacles. Collectively, its members must have relationships that extend into a wide range of crevices. They should have connections and they should be prepared to use those contacts for the benefit of the organisation. Relationships are important.

- Lend their credibility and reputation to the organisation. Being a board member of a collecting organisation may be an honour for the individual – but the relationship is two-way. The organisation either enjoys or suffers the reputation of those who lead and represent it.[12]

Powers of Governance

Whilst boards may have common purposes, they do not have common powers. Not all boards are created equal. Some boards truly govern the organisation while others are actually advisory. The only way of determining one from the other is to examine the legal instrument by which the organisation has been established.

Incorporated associations and companies:

There is no doubt that the board of an incorporated association or a company, is responsible for the governance of the organisation. The Companies Act and the Incorporated Associations Acts all make it clear that, subject to the vote of the members acting in General Meeting, the board is responsible for the governance of the organisation.

It makes no difference whether the company is for profit or not-for profit; the font of power is the board. The person responsible for day-to-day care of the collection is merely an employee of (or sometimes a consultant to) the company and is thus, eventually, answerable to the board.

Collections Created By Specific Legislation:

Here there can be no general presumption as each statute confers different powers.

The founding statute may empower the board to actually govern the organisation. For example the Australian War Memorial Act 1980 (Cth), s.9 (2) states:

(2) The Council is responsible for the conduct and control of the affairs of the Memorial and the policy of the Memorial with respect to any matters shall be determined by the Council.

However, many other statutory bodies have boards that, although they may apparently govern, are merely advisory in nature and power. For example the Archives Act 1983 (Cth), s.11 states:

(1) The Council shall furnish advice to the Minister and the Director–General with respect to matters to which the functions of the Archives relate.

(2) The Minister or the Director–General may refer any matter of the kind referred to in subsection (1) to the Council for advice and the Council may, if it thinks fit, consider and advise the Minister or the Director–General on a matter of that kind of its own motion.

It should not be overlooked that often the statute that establishes the governing body often provides that in performing its functions and exercising its powers under the legislation, the board/council/statutory body is subject to the direction and control of the relevant Minister.

Collections Created By Non-specific Legislation

There are some statutory bodies in which the board may have apparent power over the collection but in reality, the font of power lies elsewhere. This tends to occur in organisations in which the collection is subservient to the principal purpose of the organisation.

Common examples of this are museums and galleries within universities. The real power lies with the University Council, which in turn delegates some of its powers to the department within which the collection operates, and then some of those powers cascade down to the university employee responsible for management of collection. In some cases the collections have boards or committees but these are largely advisory in nature.

By way of further example, the Reserve Bank maintains a collection. Under the Reserve Bank Act 1959, the Reserve Bank Board has no specific power to establish and maintain a collection[13] but section 8A does confer a very general power that would give it the right to determine whether, as a matter of policy, the Reserve bank should maintain a collection at all.

8A (2) The Reserve Bank Board is responsible for the Bank’s monetary and banking policy, and the Bank’s policy on all other matters, except for its payments system policy (see section 10).[14]

In fact, when one considers the powers of the Governor of the Reserve Bank it would appear that the control of the collection actually sits in his hands.

12 (2) Subject to sections 10 and 10B, the Bank shall be managed by the Governor.[15]

Trusts

Assuming that the trust has been established by deed, the ultimate power of governance lies with the trustees. This is not so clear-cut when the trust is set up under some other mechanism such as a statutory trust.

For example the New England Regional Art Museum (NERAM) is incorporated as a Crown Land Reserve Trust and managed by trustees appointed by the Minister of Land and Water Conservation. Originally the Minister appointed the members of its board of management as the trustees but in May 2005, the Dumaresq Council was appointed as the Corporate Trustee. Accordingly it is the Council that governs the collection rather than its board of management. It doesn’t own the collection but it manages it as trustee for the state government.

Unincorporated Organisations

As unincorporated organisations do not have a legal entity that is separate from their members, the body responsible for the governance of the organisation is the committee or person elected or appointed by its members. The appointee is responsible to the members of the group but no one else. The powers enjoyed by the appointee are conferred by and subject to the majority decision of the group.

The role of the board

The role of the board is to provide stewardship and to ensure that the organisation is managed in accordance with its statutory and legal responsibilities. The board is the final decision making authority on all matters relating to the organisation and its activities. In performing this role the board’s activities include but are not limited to:

- Setting and reviewing strategic direction, goals and objectives

- Oversight of management and performance of the organisation

- Approving major decisions and where appropriate, making recommendations to the Minister

- Policy making

- Delegation of authority

- Succession and performance evaluation of the chief executive

- Ensuring compliance with applicable laws and policies

- Reviewing and setting executive remuneration

- Ensuring areas of significant business risk are identified, assessed and appropriately managed

- High-level allocation of resources, budgeting and planning

- Succession of the board

- Financial performance review

- Reporting to government, shareholders and to stakeholders on its stewardship

- Overview of accountability

- Approving terms of reference for board subcommittees.

- Receiving, considering and actioning recommendations from board subcommittees

- Establishment and oversight of policies

- Enhancement and oversight of stakeholder relationships

- Assessing the board’s own performance

- Approving and fostering an appropriate corporate culture matched to the organisation’s values and strategies

Of course management will be crucially involved in many of these tasks: After all, there are few board functions that are not informed and implemented by management. This is a sensitive balance in all organisations. On one hand, tt is important that the board does not allow itself to be self-indulgent by meddling in the management of the organisation: Generals don’t go onto the battlefield. On the other, it is essential that senior management recognises that, at the end of the day, it is the board that determines policy and direction of the organisation and is ultimately responsible for its oversight.

Matters to be considered by the board

The board should have a regular schedule of key issues to be considered. In order to ensure good governance, these issues should include but are not limited to:

- Approving the financial statements and annual report

- Approving the Instrument of Delegations

- Approving the business plan and budget

- Monitoring building redevelopment

- Monitoring Key Performance Indicators

- Monitoring media activities

- Conducting board evaluation

Leadership

The board as a whole provides leadership by playing an active role in shaping the culture of the organisation, often in the following ways:

- in the way it interacts with management;

- in the way it develops, in conjunction with the chief executive and senior management, strategic plans and allocates resources;

- in the way it fosters communication down, up and across the organisation;

- the extent to which individual staff are appropriately empowered to make decisions without seeking approval through the Instrument of Delegations;

- the nature and methods of applying and enforcing policies and procedures; and

- how performance is managed and rewarded.

Setting the strategic direction

It is the board’s duty to ensure that there are processes for monitoring the performance and progress of the organisation towards its goals, which are set out in the strategic plan. The board must approve the mission and strategic plan and will review progress in fulfilling its mission and the associated strategic plan. Performance milestones should be sufficiently specific to enable the chief executive to report effectively and authoritatively to the board. The strategic plan provides the basis for long term planning for the organisation. The strategic plan must be consistent with the objectives of the organisation.

The board should, from time to time, in consultation with the chief executive, management and/or staff, approve review the Mission Statement and may vary the strategic plan, as circumstances evolve.

The board approves policy as the framework for management.

Annual report

The board is responsible for the production of an annual report. The annual report provides stakeholders with performance information that demonstrates accountability for the expenditure of funds and for the efficient and effective operation of the entity. Statutory obligations in relation to the content of the annual report will vary depending on the entity structure.

Role of the chair

The chair’s role, on behalf of the board, is to protect and further the integrity of governance. In this role as leader in this process, the chair is also a servant to the board as the governing body. However, even though all the board members bear a responsibility for governance discipline, the chair as first-among-equals not only guides the process but is empowered to make certain decisions.

Equally important to formal duties outlined below is the key leadership, visionary and people management role of the chair including:

- providing leadership to help the organisation identify its goals and work towards them;

- monitoring the overall process of organisational management and policy fulfilment;

- presiding over board meetings and directing board discussions to effectively use the time available to address the critical issues facing the organisation;

- ensuring board minutes accurately reflect board decisions;

- ensuring that the board has the necessary information to undertake effective decision making and actions;

- guiding the ongoing effectiveness and development of the board and individual board members;

- acting as a mentor to the chief executive;

- identifying and recruiting people to serve on the board who can contribute to the organisation’s success;

- inspiring and motivating board members, management and staff; and

- managing conflicts at the board level.

Role of board members

Board members bear initial responsibility for the integrity of governance. The board’s proper exercise of authority is the beginning of accountability. Though the chair bears particular responsibility with respect to governance process, the entire board has to bear its individual share of responsibility. The board is not able to delegate this responsibility.

The role of board members can be broadly summarised as follows:

- The board has a direct responsibility to approve governing policies. Board members have the obligation to fulfil fiduciary responsibility, guard against undue risk, determine priorities and generally direct organisation activity. A board can be accountable yet not directly responsible for these obligations by setting the policies that will guide them.

- The board is responsible for the assurance of executive performance. Board members are obliged to ensure that the staff faithfully serves the board’s policies. If the chief executive fails to fulfil these explicit expectations, the board itself is liable. Although the board is not responsible for the individual performance of staff, in order to fulfil its accountability for the performance of the organisation, the board must ensure that staff as a whole meets the criteria the board has set.

The members of the board must also:

- discharge their duties in good faith and honestly in the best interests of the organisation with the level of skill and care expected;

- use the powers of office for proper purpose, in the best interests of the organisation as a whole;

- act with required care and diligence, demonstrating commercial reasonableness in their decisions;

- avoid conflicts of interest and not allow personal interest, or the interest of an associated person, conflict with the interests of the organisation;

- not make improper use of information gained through their position of board member;

- make reasonable inquiries to ensure that the organisation is operating efficiently, effectively and legally towards achieving its goals;

- undertake diligent analysis of all proposals placed before the board;

- serve on board subcommittees as required; and

- act as advocates and ambassadors for the organisation.

Role of the board secretary

The board secretary is generally responsible for carrying out the administrative and governance requirements of the board as follows:

- ensuring that the board agenda is developed in a timely and effective manner for review and approval by the chair;

- ensuring that board meeting papers are developed in a timely and effective manner;

- coordinating, organising and attending meetings of the board and ensuring correct procedures of governance are followed;

- drafting and maintaining minutes of board meetings; and

- working with the chair to establish and deliver best practice governance.

Role of the chief executive

Despite the governance structure of the particular organisation, the chief executive’s role broadly includes the following:

- taking and approving all and any actions and initiatives required to deliver the organisation’s strategic and operational plans approved by the board;

- ensuring transactions outside the chief executive’s delegation levels are referred to the board for approval;

- ensuring that all actions comply with the organisation’s policies in force from time to time;

- other responsibilities as delegated by the board to the chief executive;

- in conjunction with other senior management, carrying out the instructions of the board and giving practical effect to the board’s decisions; and

- meeting the legislative requirements and statutory reporting obligations in accordance with relevant legislation.

Relationship of chief executive and board

One of the often-vexed issues in the management of any organisation is the relationship between the chief executive and the board.[16]

To determine where the power truly lies, it is essential to consider the preceding section.

1. Company or incorporated associations

In a company or incorporated association the power lies entirely with the board.[17] Accordingly, it is the incorporated body, acting through its board that employs the chief executive. The chief executive is subject to the power of the board and must carry out its policies and instructions.

2. Statutory Bodies

In a statutory body, the statute determines the matter: but this can become quite complex. In many, the chief executive is employed by the Public Service and is thus answerable to a government department and ultimately the Minister. At the same time, he or she is answerable to the Board. This inevitably contains the seeds of conflict. To whom is the chief executive ultimately responsible?

The answer lies, in part, in asking:

i. Who is the employer of the chief executive?

ii. What does the organisation’s statute dictate?

For example in the case of the Reserve Bank collection, once the Reserve Bank Board has made the decision that a collection is appropriate, all decisions as to management lie firmly with the Governor.[18]

With the Australian Archives, the Act is clear that the Director-General may exercise any of the powers expressed in the Act to be conferred on the Archives. The power lies with the Director-General, not the board. The Act goes on to specify that the Director-General must comply with directions from the Minister (provided that those directions are not inconsistent with the Act.[19]

The Historic Houses Trust of NSW provides an interesting illustration of the conflict that is inherent when the chief executive has two masters. On the one hand the power relationship between its Board and its Director is spelled out quite explicitly in the Act[20]: Section 14 states that the Director is subject to the immediate control of the Board:[21]

The Director:

(a) Is responsible for the administration and management of the property of the Trust and of services provided in conjunction therewith,

(b) is the secretary to the Trust, and

(c) in the exercise and performance of the powers, authorities, duties and functions conferred or imposed on the Director by or under this Act, is subject to the direction and control of the Trust.

So in the case of disagreement between the board and the Director, it is the Director who must cede with grace. On the other hand, the Director is a public servant and thus under the control of the Public Sector Employment and Management Act 2002[22]. As such, the Director is answerable to the Ministry and ultimately the Minister and matters such as salary and conditions of employment are matters to be determined by public service mechanisms – not the Board. Such divisions are perhaps not problematic until there is a conflict between the wishes of the Board and the wishes of the government of the day. In such situations the Director is subject to the “direction and control of the Trust” whilst also receiving strong messages (if not direction) from the Ministry. At the end of the day, the answer always comes back to the question: “What do the Statutes say?” In matters relating to the statutory powers of the Trust, the Director must comply with the directions of the Trust. The Act requires it. On other matters, such as those mandated by the Public Sector Employment and Management Act 2002, the Trust has no power.

Selecting The Board

The board is the head of the organisation – both actually and metaphorically. Effective organisations have good boards; ineffective organisations have dysfunctional boards.

In many statutory bodies, the statute establishing the body will prescribe the constitution of the Board. Sometimes, the statute will prescribe the relevant skills required of board members or the categories of persons that are eligible for appointment. For example, s. 11 of the Museums Act 1983 (Vic) states that

(1) The Board shall consist of not more than eleven members and not fewer than seven members appointed by the Governor in Council of whom not fewer than half shall be chosen from persons:

(a) holding senior academic office at a university in Victoria in a discipline appropriate to the functions of the Board;

(b) who, in the opinion of the Minister, are experienced in business administration and finance; or

(c) who, in the opinion of the Minister, are distinguished in education, science, the history of human society or another field appropriate to the functions of the Board.

Board appointments are usually made by the Governor in Council on the recommendation of the Minister. Existing Board members may be consulted by the Minister in relation to new Board appointments and re-appointments.

When selecting a board you are creating a reservoir of wisdom and skills to govern the organisation by setting the strategic direction and the organisation’s objectives. The board is an invaluable source of knowledge; wisdom; contacts; vision and experience so, having regard to the objects of the organisation, work out the specific talents that are needed on the board. A good board is comprised of people:

- with the managerial, financial and appropriate cultural experience and expertise to oversee the organisation;

- of integrity and with good standing in the community who will exercise their powers and discharge their duties in good faith and for a proper purpose. Persons who will act in the interests of the organisation as a whole and not promote their personal interest by making or pursuing a gain in which there is a conflict, or the real possibility of a conflict, between their personal interests and those of the Board;

- with credibility in their field and who have a network of contacts that can be called upon so that the resources of the board are greater than the sum of its members. One of the important contributions that board members must be expected to make is to lend actively their personal reputation to the organisation. This is often overlooked. If you are establishing an organisation of national focus, the board must contain members of national reputation and networks. If it is a local community organisation, persons with influence within the local community are more appropriate. It is horses for courses. Not only must they have the reputation, they must be prepared to use it for the benefit of the organisation. Their name alone may help, but they must also be prepared to write that letter or make that phone call; in other words, actively to use their contacts for the benefit of the organisation.

- who provide independent voices. Those responsible for board appointments should avoid inviting friends and ‘yes people’. This is an issue for small, local organisations and for national institutions.[23]

- with the time to commit to the organisation. A good board member will be a busy person. When a prospective board member asks how much time will be expected of them, it is important to be frank. The true time commitment must be articulated. Productive board membership takes much more than attendance at board meetings and the reading of board papers. The strategy retreat, the sub-committee work, the lobbying advocacy and fundraising work and the associated thinking time, all adds up to a large commitment from a time-poor person.

Board members are workers. Famous names who won’t come to meetings, won’t become actively involved, won’t write that letter or make that important phone call, have no part on the board. Figureheads make good patrons but can be disappointing board members. - who offer more than the promise of money. Don’t invite someone just because they are rich. Look for people with true networks of influence which will be more valuable to the organisation.

- who provide particular skills needed by the organisation – either generally or at a particular time in its development.

Professional advice is expensive. So, unless the organisation is so rich or successful as to be able to afford professional fees, or so small-scale as not to need professional skills, the group might invite the necessary expertise onto its board. For example, it can be invaluable to have an accountant in the group to assist in budgeting, advising on fund raising strategies, reviewing expenditure and preparing financial reports. Similarly, as most organisations these days have to raise money of their own it is almost always important to have a well-connected businessperson on the committee. Such a person will not only give sensible practical advice on finance and administration but will also be able to make personal contact with potential sponsors.[24] - with relevant experience in the area. As one of the most important functions of any board is to determine policy, it is vital to have a strong representation of persons with relevant experience in the area. Knowledge and practical experience is more important than fine intentions.

- who provide the organisation with a balance of skills on the board. A balanced board includes persons who represent a range of constituent interests.[25] Balance should also take into account other matters: gender, race, geography, age – but it should be RELEVANT SKILL that is the determining factor.

- provide corporate continuity. It often takes a board member the best part of a year to find their feet and become a truly effective contributor. Accordingly, it is disadvantageous if the board has too many experienced heads leaving at the same time and too many novices joining the board. Regular renewal and rejuvenation is important and should be planned so that the board remains a healthy mix of experience and new ideas.

Summary of Skills

- managerial, financial and appropriate cultural experience and expertise

- integrity and good standing in the community

- credibility in their field

- a network of contacts

- independent voices

- time to commit to the organisation

- offer more than the promise of money

- particular skills needed by the organisation

- relevant experience in the area

- provide a balance of skills and attributes on the board

- corporate continuity

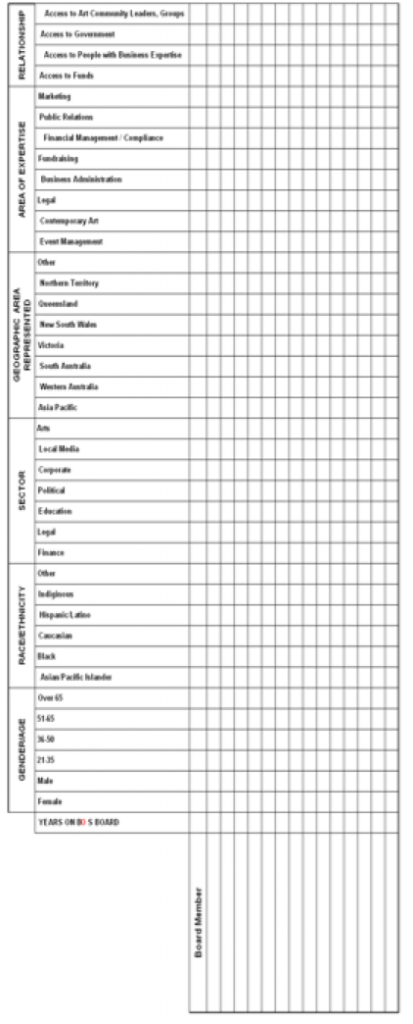

The likelihood of identifying the right person is promoted by using a ‘skills matrix’:

SKILLS MATRIX

The Ask

The identification of good potential board members and the likelihood them accepting can be enhanced by good process:

i. Whether the organisation is a large government body or a small volunteer one, the selection of board members should be done using a skills matrix to ensure that the appointment meets the identified needs of the organisation. This matrix will vary from organisation to organisation and, even with the same body, will vary from time to time.

ii. When you have created a skills matrix that suits the needs of the organisation, under each of the required skills, make a list of the names of people who would be the very best you can think of. Review ALL appropriate names – not just people you know.

iii. Take some time to think about that list: consider the strengths and weakness of each of the potential names. Diplomatically ask around about each candidate. People who have worked with them will have views about their true value and effectiveness (this may be quite different from their public persona). Sometimes you will find that although they are well known and well regarded in their specialist field, they have a track record of being divisive or lazy board members. All that glitters is not golden.

iv. Ask only the best. Don’t worry if you don’t know them personally. Nobody minds being invited onto a board. It is usually flattering. Get an appointment and do your pitch in person. It is much more effective than just writing a letter or talking on the phone.

v. Give the candidate the material they need to make an informed decision. They need to know why you believe they would make a useful contribution to the organisation and what would be expected of them.

vi. If your first choice says ‘no’, don’t be disheartened. It’s not personal. Instead, ask them for names of persons that they think might be suitable. They may well come up with a suggestion that is fantastic but one that you hadn’t considered or hadn’t dreamed would be interested. (If the suggestion is someone you don’t personally know, ask if you can use his or her name to make contact. It makes the next approach so much easier.)

Helping The Board Work For The Organisation

The health and success of an organisation reflects the effectiveness of the Board. There just aren’t any cot-case organisations with terrific Boards. This section discusses some of the ways that an organisation can get the most out of their Board and ensure that their board works as well as it should.

The care and feeding of board members

Board members give their time generously and without much return. Nobody accepts appointment to a board for the money. They are making a voluntary contribution to a community activity that they really care about. They are almost certainly very busy and it is important that they are made to feel welcome, involved and acknowledged. If they are to contribute to their maximum ability to the benefit of the organisation, there are some basic steps that every organisation should put in place.

Introduction procedures for new board members

Every organisation must ensure that there are clear handover procedures for the induction of new members onto the board. A good handover ‘package’ would include:

i. a personal brief as to what is expected of them;

ii. a copy of the relevant legislation or constitution governing the organisation;

iii. copies of the latest annual report, strategic plan, corporate/management plan, business plan, the financial reports and papers and minutes of the last few meetings;

iv. the policies of the institution including Ethical Conduct Policy and Code of Conduct;

v. guidelines as to discipline and lines of communication,

vi. a list of key personnel, and

vii. any other documents of which the new Board member should be aware.

The new board member should be introduced to management and the staff and, if there are premises, shown around the offices. Every new board member should have a feeling of belonging.

Then, every three or four months, the chair should contact each member individually and have a brief chat as to how they think the organisation is going, whether there are any issues that need addressing and, most importantly, how they feel they are contributing to the organisation. This gives the chair the opportunity to hear more private views that may need to be expressed and acknowledged and also permits the chair the opportunity to deal with any problems or issues, such as lack of performance, that may be embarrassing to discuss at the board meeting.

Assignment of responsibilities

Perhaps the most important internal function of any board is the definition and assignment of individual responsibilities to directors. In all cases, because a board can only function by delegating certain tasks to individuals or subcommittees, it is important for boards to consider how to go about delegating tasks in the most effective manner. This also involves an understanding of the appropriate limits that should be placed on individual board members actions and responsibilities.

When assigning responsibilities you must make sure that:

i. The best use is being made of their expertise and contacts;

ii. Individual board members are being realistic about the level of responsibility they can take on. (The Chair must be careful not to overload any particular board members. They are volunteers. That generosity must not be abused or they will soon lose the fire in their belly. Jobs need to be spread around between board members. If they can’t be, it may well indicate that you need to review the make-up of the board);

iii. The responsibility should be clearly articulated so that there can be no mistake as to the commitment being undertaken;

iv. There should be a reporting line and a time line put against each task;

v. Each task should be fully minuted so that the responsibility is recorded and both the individual and the Board itself knows that there will be a report on the activity at the next meeting.

Decision making, defining policy and setting strategy

When looking at the policies and strategies of an organisation, Board members must ask themselves:

i. Does our organisation have a written Statement of Objectives that is clearly articulated, understood and accepted? Without it, the organisation has no basis for determining its actions and its priorities. Without it, the senior management of the organisation has no tiller with which to guide its day to day decisions;

ii. How long is it since the organisation’s policies and priorities were reviewed? Unless these are regularly reviewed, the organisation may become stagnant or the victim of conflicting and incompatible priorities for resources.

iii. How are policy reviews undertaken? Is the Board involving all the people who have a contribution to make in the policy development process? Is it using the best available techniques? All too often, boards make policy without sufficient involvement of their members, their staff, their funding bodies and other groups who may have real contributions to make to the process. The involvement of select outsiders may assist the board to gain a wider perspective of their own organisation. Few boards have the internal skills to carry out thorough policy reviews using only their own internal resources and the board could consider seeking the assistance of a professional facilitator to assist in the process.

iv. How are strategies determined? While the responsibility for determining strategy lies with the board, in most cases it is management, the staff, volunteers and members who will carry out the strategies and in many cases it is management that actually designs the strategies. It is one of the areas in which there is great potential for conflict with management but it is important that the board oversees the development and implementation of the organisation’s strategies. It is the board that must call for them, query them and, when satisfied, approve them. Later, it must evaluate and amend them. This remains an on-going process.

Setting limits and creating communication channels

One of the frequent sources of conflict in organisations is the absence or breakdown of proper communication channels. One could write books about good communication within organisations, yet the basics are simple enough.

The chair is responsible for the conduct and productivity of the board members. The chief executive services the board and inevitably has a relationship with the board members but it is the chair, not the chief executive, who controls the board and its members.

Similarly, it is the chief executive who controls the employees of the organisation. This is not the function of the board or the chair. If the staff is dysfunctional, it is the task of the chief executive to fix it. That is not the role of the board, or any of its members.

Communication between the chief executive and the board should always be through the chair. (This may be delegated to the chief executive as to purely administrative matters, but the line is a thin one. When in doubt, the chief executive should always seek the Chair’s leave before communicating with members of the board. Similarly, outside the boardroom, members of the board should raise matters of concern with the chair rather than the chief executive.

Where a government department is the highest form of authority of an organisation, the channels are often blurred because communications between Ministry and chief executive are so frequent and so often ordinary. However, it is good governance practice if the Ministry remains conscious of the importance of communication channels and involves both the chief executive and the chair in any matters of significant consequence to the organisation.

In reverse, when a Ministry requires a direct reporting relationship with the public servant chief executive it must remain conscious and sensitive to the inherent conflict that it is imposing on the chief executive. The Ministry should remain conscious of the benefits in requiring that both chair and chief executive participate in any significant communications between the Ministry and the institution.

Many board members need to understand better the nature of and limits to their relationship with employees, volunteers, members, and with the public. Each of these relationships is potentially complex and may give rise to difficulty, whether an organisation is large and has numerous employees and a senior management, or whether it is a small organisation that is not much larger than the board itself.

There should be clear guidelines as to what a board member may or may not do in relation to management, staff, members and volunteers. For example, in terms of dealing with staff – the organisation should have written guidelines articulating the staff selection, instruction, reporting and review procedures. The Board, as a collective entity, has responsibility for ensuring that appropriate staff policies and procedures are in place. It is not each board member’s individual duty (or right) to get the staff to do what he or she individually thinks is best.[26]

The prudent board also holds annual or semi-annual confidential interviews with senior management so that it can learn more about the needs and expectations of those controlling key sections of the operation. A sub-committee of the board may undertake this; the Chair sometimes does it. In larger organisations (where resources permit) an outside consultant might conduct the interviews so that the staff feels more able to speak freely about difficult matters without the fear of later retribution.

Simple communication protocols are important. If they are complicated, they are forgotten or ignored. When a simple approach is maintained, greater clarity, control, discipline and effectiveness is maintained. There is less opportunity for miscommunication and mischief.

Delegation

The delegation of power and authority is another form of setting limits – whether it be on sub-committees or on individual board members who are delegated responsibilities.

If boards have one problem that is greater than almost any other it is in the delegating of power and authority. Because a corporate body can only act by a series of delegations it is necessarily and fundamentally dependent upon the quality of those delegations. Three common problems arise with delegations: invalidity, vagueness or, quite simply, they are forgotten.

Invalidity usually arises because the delegation is outside of the powers of the board, or outside of the objects of the organisation, as set out in the constitution;

Vagueness arises because the terms of the delegation have been insufficiently articulated.

Oversight usually occurs because the delegation has not been formally or clearly recorded in a special delegations book (and not just in the Minutes Book).

When establishing a delegation of power the board needs to ensure that the constitution allows for that the authority to be delegated. Once that has been established, when setting out the extent of the delegation it is important that the parameters are clearly defined and that everyone knows what is expected. It is prudent for the board to approve an instrument of delegation setting out the relevant delegations to sub-committees, management and individual staff for the day-to-day operation of the organisation. The instrument of delegations should be reviewed annually to ensure that the delegations remain relevant and at appropriate levels.

In relation to establishing delegations outside of the instrument of delegations in relation to a project or for a specific purpose, the board needs to:

i. Make it clear whether the subcommittee or individual is being given the power to make a decision or whether it is merely authorised to make a recommendation to the board that in turn makes the decision;

ii. Ensure that the nature and burden of work involved is appropriate – indiscriminate assignment of work to others is not delegating, it is dumping, and giving orders is not the same as delegating;

iii. Select a capable person;

iv. Provide a specific time frame through each of the project’s phases;

v. Establish specific review dates throughout the entire time frame; and

vi. Record the fact of the delegation and its ambit. Verbal instructions should usually be followed up in writing so that the memo can be referred to later.

Remember that while the ultimate responsibility stays with the delegator, true delegation implies that the individual, subcommittee, or subordinate is given the authority to do the job: that they can make independent decisions and have the responsibility for seeing the job done well. When a board delegates a task it should avoid unnecessary interference. If you have selected the right person and given clear instructions, let them get on with it.

Sub-committees

Even the smallest of collecting organisations need sub-committees. It is inefficient for the board to undertake all of the work that must be done. Much of the work can be delegated to small groups with particular expertise.

Common sub-committees include: Audit[27]; Marketing and Promotion; Finance[28]; Fundraising[29]; Collection Management[30]; Sponsorship and Philanthropy[31]; Risk Management[32]; Emergency Planning[33]; Contract Committee[34]; ICT Committee[35]; Workplace Relations Committee[36].

Obviously not all organisations require all of these sub-committees although it would be a very rare organisation that would not benefit from at least two or three of them. Even the smallest of collecting organisations benefit from sharing the workload and expanding the available skill base.[37]

A committee system allows for specialised, skilled and interested people to work efficiently. Accordingly appointment to sub-committees is skill-based although the actual machinery for appointment is very dependent on the constitution of the organisation. For example, in some statutory organisations the Act states that the chair or president of the Board is an ex officio member of every committee of the board[38]. This does not mean that the chair of the board is automatically the chair of every committee. That would be foolhardy. It is a much more advantageous to appoint the leader in that specialty area to the leadership role on the committee. If there is an Executive committee the chair of the board would be expected to also chair the Executive Committee but it would be most usual for the chair of the board to head any other sub-committees. After all, each of the committees must report to the board and that reporting process is one that is controlled by the chair.

In most organisations it is not necessary for all of the members of a committee to be members of the board. Although the committee’s powers are delegated from the board, it can be made up of members who are not also board members. Indeed, this can be very healthy for the organisation: It permits the organisation to leverage its support in the community by inviting into the engine of the organisation a wider range of expertise and support than can ever be delivered by the board members acting alone.

Relationship of the board with its committees

The relationship between the board and the sub-committees should be one in which the committee supports and assists the work of the board. The board that remains ultimately responsible for the governance of the organisation and no amount of delegation can change that.

The power of the committee flows from the board. It is the delegation from the board that confers and delimits the power of its committee. Most committees are advisory and only have the power to make recommendations: They do not have the power to make final decisions on behalf of the board. There needs to be very special reasons to justify giving a sub-committee the power to commit the organisation to any obligation, liability or strategy. Their power is usually limited to advise and make recommendations to the board. Whether the board accepts that advice is another matter: If the board choses not to do so, it may be brave but it is not acting beyond its powers.

Given this, it is essential that care be taken in articulating the precise task being delegated to a sub-committee. This will usually include some basics as to expected milestones and the timetable for reporting to the board. Strong sub-committees are good things but they must remember that they are the handmaidens of the board.

As mentioned above, there are usually no rules as to the composition of the sub-committees: Members are usually appointed at the will of the board. Although some statutes may make the chair of the board an ex officio member of every sub-committee[39], the chair (as leader of the board) should always have the right (but not the obligation) to attend sub-committee meetings[40].

The CEO of the organisation does not have the ‘right’ to attend sub-committee meetings[41]. Sub-committees are creatures of the board, not the administration. If the CEO wants to attend particular sub-committee meetings, he or she should be appointed to the sub-committee by the board. In many cases the CEO attends ‘by invitation’ rather than ‘by appointment’. In other words the chair of the sub-committee invites the CEO to attend and participate. That invitation is discretionary and can be withdrawn or suspended at any time.

Confidentiality

One of the most frequently occurring issues in not-for-profit organisations is getting board members to understand that what transpires at a board meeting is confidential information and should not be revealed without the permission of the board. Except where one is required by the Law to reveal such information, there is no excuse for breach of this fundamental rule.

Some organisations require their board members to sign non-compete and/or confidentiality agreements. This is not common but can be a useful way of emphasising to the board members that the discussions of the board table are supposed to stay within the boardroom.[42]

It is more common (and perhaps more appropriate) that the organisation have a written confidentiality policy that has been endorsed by the board. Adherence to this policy should be a condition of staff employment contracts and board appointments. If should be made very clear that those who are unable to comply with the policy, should resign (or failing that, be removed.)

These are standard fiduciary requirements of board membership. As part of their induction process, new board members should be given a copy of such policies and have them explained.

Invitees to board meetings

Board meetings are neither social occasions nor an appropriate place to conduct board-management discussions. Although the CEO (and in larger organisations the legal counsel) might be expected to attend board meetings, the presence of any employee is a matter of privilege not right.

There are many situations in which it is appropriate that all non-board members (including the chief executive) be required to leave the room. Basically, if there is any likelihood that the presence of a non-board member may inhibit the discussion of the board, that non-board member should be asked to leave the room.

It is not generally appropriate to allow members of the general public to attend board meetings (although there may be some local councils that have rules requiring it.) Board members must be able to speak freely and with candour. Board participation is not a spectator sport.

Reviews and self-evaluation process

Just as employees need regular reviews, so too do board members. Self-evaluation is important as it provides feedback on the working of the board and identifies areas requiring improvement. In the interests of good governance and to maintain and continually improve the excellence of governing, the board should undertake an annual assessment of its performance, the performance of individual board members and that of its sub-committees.

Larger organisations usually retain an outside consultant to conduct the review but in smaller organisations, the task is left to the Chair. This gives the board member the chance to reveal any concerns or criticisms that he or she may have about the board, the Chair, the organisation and their own performance. It also gives them the opportunity for confidential feedback as to their own performance.

Often overlooked, it is important the Chair’s performance also be reviewed. It is important the Chair take this opportunity to improve performance by hearing the views of all other board members.

DUTIES OF PEOPLE IN RESPONSIBILITY

Every person in a position of responsibility has duties imposed by law. For example, some museum organisations are a part of a government department and their employees are departmental employees bound by various laws such as the Public Service Act, Audit Act, Finance Directions and so on.

Other institutions may be statutory bodies, established and funded by government but operating under their own statute. Those established by Local Government will operate under different rules again, including the Local Government Act.

Then there are companies established under the Corporation Law, incorporated associations established under the Incorporated Associations Act and trusts which are governed by the Trustee Act and associated legislation.

Employees of all tiers of governmental institutions may be hired as government employees or under contract, while employees of companies, trusts, and associations are all employed under a common law contract of employment. These will all impose particular responsibilities in addition to those set out in the legislation.

The following can only provide a guide to board member rights and responsibilities and does not try to discuss the complexities of the numerous individual circumstances.

Duties of Board Members of Statutory Bodies

1. The Statutory Duties

The statute that establishes an institution also sets out the basic duties of those responsible for its governance. Necessarily, each such institution is different and all employees and board members should be familiar with the terms of their statute.

2. The Duty To Observe Natural Justice

Besides the provisions of the statute that establishes an institution, those invested with power have an obligation to observe the rules of natural justice. These include the duty to act fairly, to take into account all relevant matters and to omit all extraneous considerations.

Each board member’s duty is to the institution. Even if he or she is on the board or council as a representative or nominee of a particular interest group, or has a particularly burning political, ethical or other position, the over-riding duty must be to the institution and the purposes for which it is established. A board member must not be compromised by promoting interests that are extraneous to those of the institution.

Duties of committee members of unincorporated associations

Because an unincorporated association cannot hold assets in its own right, any member that looks after property or money belonging to the association does so as a trustee on behalf of the association. A trustee must not place his or her own interests above the purposes of the trust because the trustee has a fiduciary duty to the objects of the trust. A trustee’s obligations are the most onerous of all. (Refer to the section “Duties of Trustees” below.)

Duties of management committee members of incorporated associations

The responsibilities of the Management Committee of an incorporated association will be set down in the relevant state legislation.

The Management Committee will be responsible for holding regular meetings, as well as an Annual General Meeting and the Public Officer of the association will be responsible for filing the association’s annual statement with the appropriate government department.

It is also important to remember that while the formation of an incorporated association does provide protection to member of the committee and the association from liability for debts incurred by the association, this is not unlimited. Individual committee members could be held personally liable for debts if they authorise expenditure without having reasonable grounds to expect that the debt can be paid.

The legislation governing incorporated associations also provides for the imposition of fines and other penalties if the committee members actions amount to fraud. This responsibility will not be imposed on members of the Committee who did not authorise or consent to the expenditure being incurred. However, if a Committee member ought to have been aware of the debt, for example if they are responsible for overseeing a particular area of the association’s operations and they fail to keep informed about that area, they could be held responsible for a debt, even if they did not know about it.

The duties of members of a management committee of an incorporated association under the common law are the same as those of the members of a Board of a company limited by guarantee (considered below). In several States the legislation has clarified the nature of these duties. It is essential that all members of a Management Committee are aware of their responsibilities under the relevant legislation, acquaint themselves with the rules governing the association and keep informed of the activities of the association and its members.

The checklists at the end of this chapter are applicable to all members of boards or management committees, regardless of the type of organisation.

Common Law – Fiduciary Duties of a Board Member

Board members are subject to specific statutory obligations as well as being subject to obligations at common law which are similar to the responsibilities of a company director under the Corporations Law. The key common law fiduciary duties of the board can be summarised as follows:

Duty to exercise due care and diligence

This means making proper investigations and inquiries into matters relating to the management of the organisation, particularly in relation to its financial operations to ensure solvent trading. It is the board members’ duty to ensure that there has been adequate assessment of major risks which the organisation faces. Risk management is not just about accounting controls, nor is it restricted to insurable risks. Risk management requires three conscious acts on the part of the Board:

- Identifying risks

- Procedures for handling risks

- Monitoring quality of management and performance against plans.

Board members are required to exercise the degree of care and diligence in performing their functions to the standard of skill that may be reasonably expected from a person of his or her knowledge and experience, and that which a reasonable person would exercise in a like position.

The duty to act with reasonable care and diligence requires all board members to:

- Possess a minimum objective standard of competency, including a basic understanding of the board’s business and its financial statements

- Regularly review the financial statements

- Keep informed of the board’s activities and generally monitor the board’s affairs and policies

- Attend board meetings regularly

Board members are entitled to rely on information or advice given or prepared by others such as management, professional advisers or board subcommittees where the reliance is made in good faith.

Duty to act honestly, in good faith and for proper purpose

Board members must exercise their powers and discharge their duties in good faith and for a proper purpose. A board member must act in the interests of the organisation as a whole and not promote his or her personal interest by making or pursuing a gain in which there is a conflict, or the real possibility of a conflict, between his or her personal interests and those of the board. The key to this obligation is to avoid conflicts of interest between a board members private interests and the exercise of their duties as a Board member.

The duty not to make improper use of information or position.

Board members must not use their position or information gained through their position to gain an advantage for themselves or someone else or cause detriment to the board.

Duties of directors of companies limited by guarantee

1. Introduction

The responsibilities of a company director are the same, regardless of whether the company is profit making or a non-profit organisation. This point was made clear by the National Safety Council Case (Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Friedrich (1991) 5 ACSR 115), a case that struck fear into the heart of every person sitting on the Board of an arts organisation. There, the elderly, respected Chairman lost his savings, his reputation and his health as a result of the actions of the chief executive when he was found liable as a director for an extraordinary amount of debts incurred without his knowledge.

THE DUTIES OF A DIRECTOR OF A NON-PROFIT COMPANY

- To act honestly, and in the best interests of the company;

- To not make improper use of information;

- To not make improper use of their position;

- To avoid conflicts of interest;

- To act in good faith, and for a proper purpose;

- To demonstrate reasonable skill in the performance of their duties;

- To exercise reasonable care and diligence when making decisions; and

- To ensure that the company does not continue to operate after it has become insolvent.

In recent years the courts have become much stricter in imposing liability on ‘passive’ directors, directors that through ignorance or inactivity fail to carry out their duties properly. Board members or directors can no longer say they “didn’t know”. The courts have held that board members or directors should have known. If you take on the responsibility of board membership, you must take an active interest and care in the operation of the company. You cannot just let others look after business. If you do, you are inviting personal liability.

Directors of companies that fail to carry out their duties may lose the protection of limited liability and become personally liable for debts incurred by the company. A member of a board has a duty to keep informed about the operations of the company and must have adequate skills to cope with the demands of the company management. It is no longer sufficient to simply do one’s best and hope for the best.

2. Duties Of Directors, Board Members, And Management

It is generally true that directors and employees enjoy very limited liability for losses incurred by their company. However, the Corporations Act does lay down a number of situations in which the corporate veil may be lifted to expose the individual not only to prosecution and penalty but also to a personal civil liability. In considering the following paragraphs it is important to note that the legislation defines “officer” to include the directors, secretary or executive officer of the corporation and anyone from whom those people customarily take direction. It is also important to note that a breach of any of the next four duties can result not only in a court order prohibiting you from managing a corporation; it can also expose you to civil penalties up to $200,000.

i. The duty of honesty: An officer of a corporation must act honestly in the exercise of his or her powers and duties.

ii. The duty to take reasonable care and be diligent: People are often invited to join a board merely for their famous name. However, as one judge put it, “a director is not an ornament, but an essential component of corporate governance.” [43] They run grave risks if they do not actually read the board’s documents, attend its meetings and diligently oversee the operation of the company. It is no answer to say that “I was too busy to get to meetings”, or “I don’t understand figures”. Board membership is not appropriate for those wishing to lend their name to a cause but not intending to be involved personally. Those people make good “patrons” but their membership of boards does not assist control of the company and exposes them to potentially enormous liability.

This was made enormously clear in the recent Centro Property Group litigation.[44] This is the most important case on directors’ duties for some time and it is worth quoting a key passage in which Justice Middleton said:

‘The case law indicates that there is a core, irreducible requirement of directors to be involved in the management of the company and to take all reasonable steps to be in a position to guide and monitor. There is a responsibility to read, understand and focus upon the contents of those reports which the law imposes a responsibility upon each director to approve or adopt.

All directors must carefully read and understand financial statements before they form the opinions which are to be expressed in the declaration required by s 295(4). Such a reading and understanding would require the director to consider whether the financial statements were consistent with his or her own knowledge of the company’s financial position. This accumulated knowledge arises from a number of responsibilities a director has in carrying out the role and function of a director. These include the following: a director should acquire at least a rudimentary understanding of the business of the corporation and become familiar with the fundamentals of the business in which the corporation is engaged; a director should keep informed about the activities of the corporation; whilst not required to have a detailed awareness of day-to-day activities, a director should monitor the corporate affairs and policies; a director should maintain familiarity with the financial status of the corporation by a regular review and understanding of financial statements; a director, whilst not an auditor, should still have a questioning mind.

A board should be established which enjoys the varied wisdom, experience and expertise of persons drawn from different commercial backgrounds. Even so, a director, whatever his or her background, has a duty greater than that of simply representing a particular field of experience or expertise. A director is not relieved of the duty to pay attention to the company’s affairs which might reasonably be expected to attract inquiry, even outside the area of the director’s expertise.’ [45]

The judge made it very clear that the directors could and should have made enquiries of the financial statements as part of their duty. If they had been aware of the relevant accounting standards they would have recognised the errors in the financial statements. This case shows that if directors are to exercise their duty of care competently, they must be financially literate.[46]

The directors’ duty of care also requires that they take a diligent interest in the company’s affairs and exercise an enquiring mind. This does not mean that they have to get their decision right, rather that they go about the decision-making process in an engaged and competent manner.

iii. The duty not to make improper use of information acquired as a result of your position with the corporation. A board member or an employee owes primary loyalty to the well being of the organisation. Thus, information learned as a result of one’s position in the company must be applied to benefit the company and personal interests must take second place.

iv. The duty not to make improper use of your position. No director or employee is allowed to make improper use of their position to gain personal advantage, or to advantage anyone else, or to disadvantage the corporation.

v. The duty of a director to disclose conflict in contracts. It is important to emphasise that it is both common and permissible for directors to have conflicts of interest. However, the Corporations Law demands that a director, who is in any way interested in a contract or proposed contract, must declare that interest. This must be done in a meeting of the board as soon as is practicable after the relevant facts are known.

This does not prevent that person from speaking to the subject of the contract or even voting on it. It merely provides the other directors with the context from which the person speaks. The directors can give those comments the weight that they deem appropriate in the declared circumstances.

Often, of course, when a potential conflict of interest arises it is most appropriate for that director to offer to leave the room until the issue is decided. The other directors may then accept that suggestion or invite the interested person to remain. That, however, is a matter of etiquette not law. All that one need do is declare the interest.

“Interest” is interpreted very broadly. It may arise through board membership, employment, consultancies, family connections, investment, and so on. To lessen the repetitious intrusion of such declarations into the business of the board, a director may give a general notice of interest to the effect that he or she is an officer, director or member of a specified corporation or firm and is therefore to be regarded as interested in any contract which may be made with that corporation or firm.

For this reason, it makes good sense for all board members to disclose, at the first board meeting after each Annual General Meeting, all current employment, directorships or memberships. It is interesting for the other board members, it saves the tedious interruption of board business by directors making repetitive declarations of interest, and it lessens the risk of receiving a $1,000 fine or three months imprisonment. If it is discovered that a director has not disclosed a conflict of interest, the contract may be voidable by the company.

3. Liability Of Directors And Employees To Pay Company Debts

As a general rule, incorporation protects the individuals from personal liability. If the company goes to the wall, its directors and employees may walk away with their reputations in tatters but their bank accounts intact.

However, if a person fails to act honestly or act with reasonable care and diligence, or makes improper use of either information or position, the corporation can sue that person and recover any profit that any person made, and any sum that the corporation has lost as a result of the failure.

(i) The Statutory Position

Section 592 (1) of the Corporations Act states that if -

“(a) a company incurs a debt, whether within or outside the State; and

(b) immediately before the time when the debt is incurred there are reasonable grounds to expect that either -

(i) the company will not be able to pay all its debts as and when they become due; or

(ii) if the company incurs the debt, it will not be able to pay all its debts as and when they become due; then any person who was a director of the company, or who took part in the management of the company, at the time when the debt was incurred is guilty of an offence and the company and that person or, if there are 2 or more such people, those people are jointly and severally liable for the payment of the debt.”

The legislation goes on to provide a defence for defendants who can prove that such debts were incurred without their implied authority or that they could not have had reasonable cause to suspect that the company would not be able to pay its debts when they came due.[47]

The Corporations Act provides both civil and criminal sanctions for the breach of this section. If criminal proceedings are commenced the defendant is liable to a $5,000 fine or one year in prison, or both. If civil proceedings are started, the directors and senior employees and any other persons involved with the management of the company may be held personally liable for the company’s debts.

- (ii) Implications

The duties imposed on directors and other officers can have serious implications for all cultural organisations, for nearly all live according to the hazardous and uncertain principles of government funding. Quite simply, most public cultural organisations in Australia lose money and depend for their continued existence upon subsidy. The danger is that one year’s funding does not guarantee a grant the next. Nor can the organisation assume that the level of grant will remain as high, let alone increase with inflation or in line with an expansion of program needs.

For years, the directors and management of such organisations have accepted this position and blithely entered on-going commitments on the assumption that there would always be public money available at (at least) the same level as the previous year. Now, with this imposition of personal liability and the increasingly restricted budgets available to funding bodies, such assumptions are dangerous.

For example, no publicly funded organisation should employ staff for a fixed term of more than a year without ensuring that the contract is conditional upon continued and adequate funding. Otherwise, if funding is cut off, there is a real (if remote) possibility that the board members may find themselves personally liable for paying staff salaries. Leases on premises raise similar problems. [48]

Part of the difficulty lies with policies of funding bodies. They all warn client groups that on-going funding is not guaranteed and some have warned of the onerous liability under the Corporations Act. Aware of this potential danger, funding bodies will generally put an organisation on notice or review before cutting off funding. Similarly, the introduction of triennial funding has considerably reduced this danger for many organisations.